The One Statistic Powering The Canes' New Philosophy

The Carolina Hurricanes have been an anomaly in the defensive zone for years, and a recent tweak to their recruitment strategy will make them even more of a force to be reckoned with.

We’ve reached the dog days of the offseason; a far cry away from the always action-packed July 1st, yet still a long way to go from Opening Night and training camp. This article was supposed to come out near the start of July, but with ~$11m in cap space and a glaring hole at 2nd line center, I figured there was still one more move left to be made. It turns out that move was re-signing Jackson Blake until his age-30 season; it’s a great move, just the one I wasn’t anticipating or expecting. So, here I am, typing this out to fill the gaping chasm of hockey content in August — where I promise you the front office will swing a blockbuster deal for Marco Rossi or Mason McTavish as soon as I press the publish button.

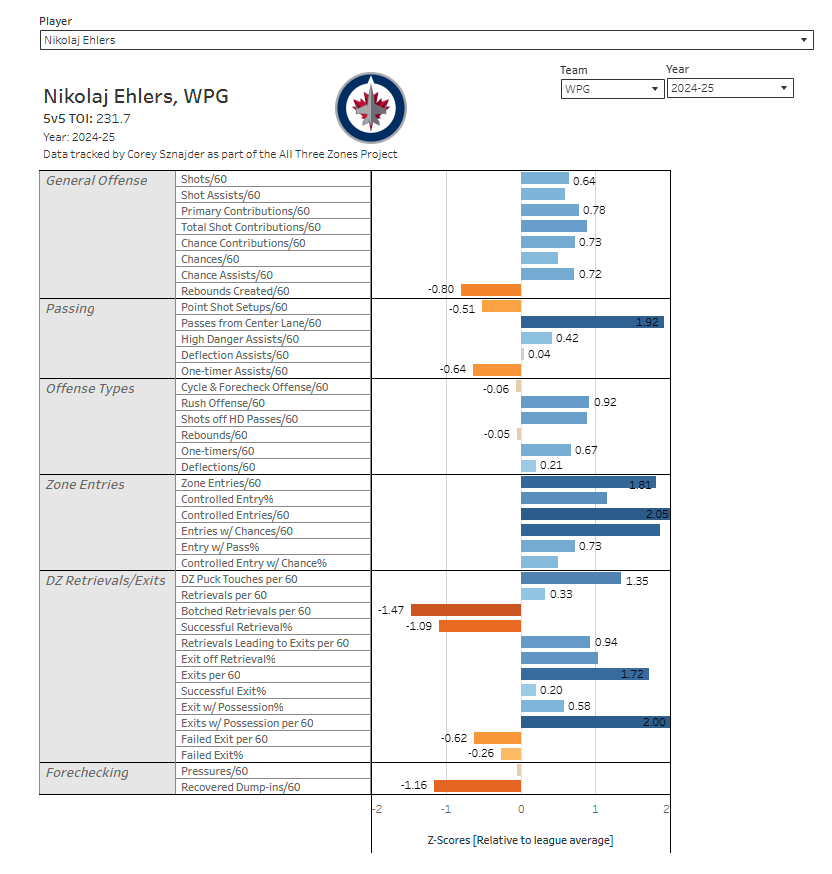

This was originally supposed to be an article about K’Andre Miller, where I’d talk about how the Rangers botched his development and how the skill set is already there for the Canes’ coaching staff to go to work on. It wasn’t until I did a brief study of his microstat profile that I found a discernible trend.

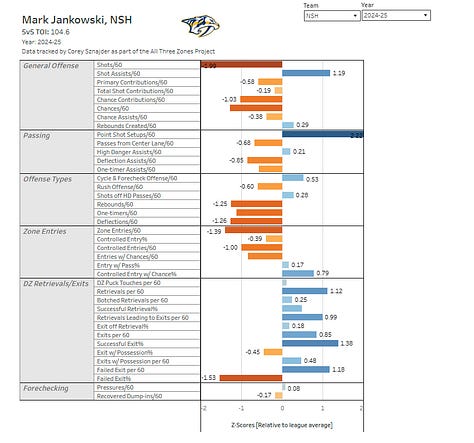

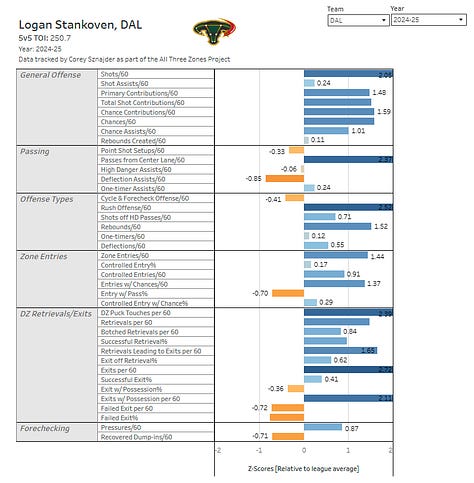

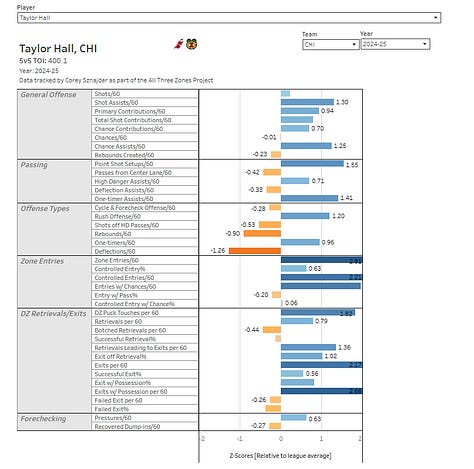

For those new to this type of data, you don’t need to have in-depth knowledge of statistics or analytics to analyze this visualization. All you need to know (at least for right now) is that blue signifies good/above-average, and red signifies bad/below-average. What jumps off the screen to you? It could be the overwhelming amount of red, particularly when it comes to his performance regarding zone entries for and against. For me, it was the one area he succeeded in the most (or if you’re a pessimist, the one area of his game that he didn’t completely suck at): defensive zone retrievals and exits. Unlike the majority of the other statistics featured on the graphic above, the ability to cleanly exit the zone with possession and retrieve pucks is a consistent, repeatable skill that is much more resistant to year-by-year variance than other defensive statistics, such as zone entry defense. In layman’s terms, it’s a statistic that tells more about the actual skill of a player, as opposed to how they are deployed. It’s a skill that coaches at the highest level observe and make those types of players the focal point of the system, rather than just a mere component of it.

Over the last handful of seasons, there have been two organizations that have been at the forefront of completely revitalizing defensemen and getting them to play at peak performance: the back-to-back Stanley Cup Champion Florida Panthers and, of course, the Carolina Hurricanes. They’ve maintained their success through three ways: being a stonewall against controlled zone entries and rush opportunities, always retrieving the puck in the defensive zone, and being able to consistently get the puck out of the zone when needed. That last topic is where things start to get interesting.

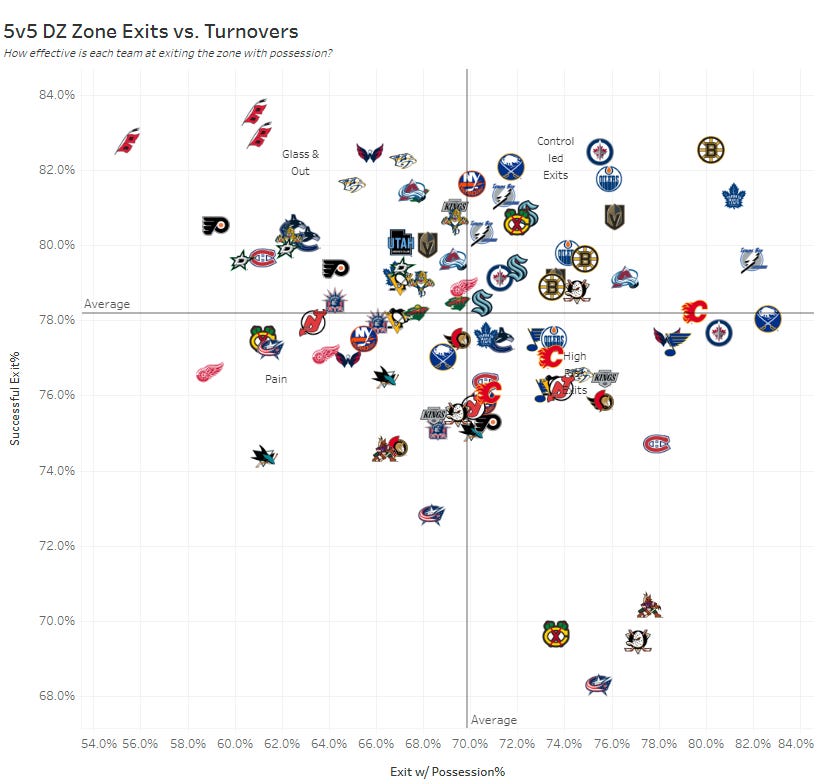

In the last three seasons, the Carolina Hurricanes have led the league in successful exit percentage by a pretty wide margin. They’ve also consistently been dead last in exit with possession percentage in that same time frame. It’s an anomaly of sorts, one that makes you question how that’s even possible in the first place. The answer is simple: if there’s any hint of opposing pressure, they just get the puck on the blade of their stick and clear the zone from off the boards. It’s an effective strategy, particularly against teams with an inefficient forecheck, that starts showing cracks deeper into the postseason, where play gets tighter and space gets narrower. That’s where the need for defensively responsible players who have the speed and skill to transition the puck out of dodge comes in; acquiring Miller for the back end was only the beginning. This is how the Carolina Hurricanes not only plan to revolutionize their defensive zone strategy but their talent acquisition as a whole. Let’s dig in.

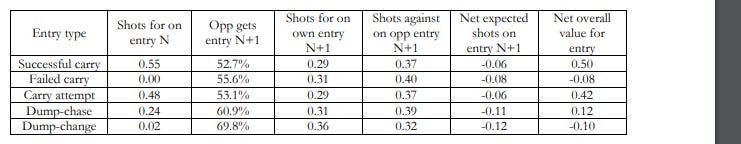

The Transitional Offense Spectrum

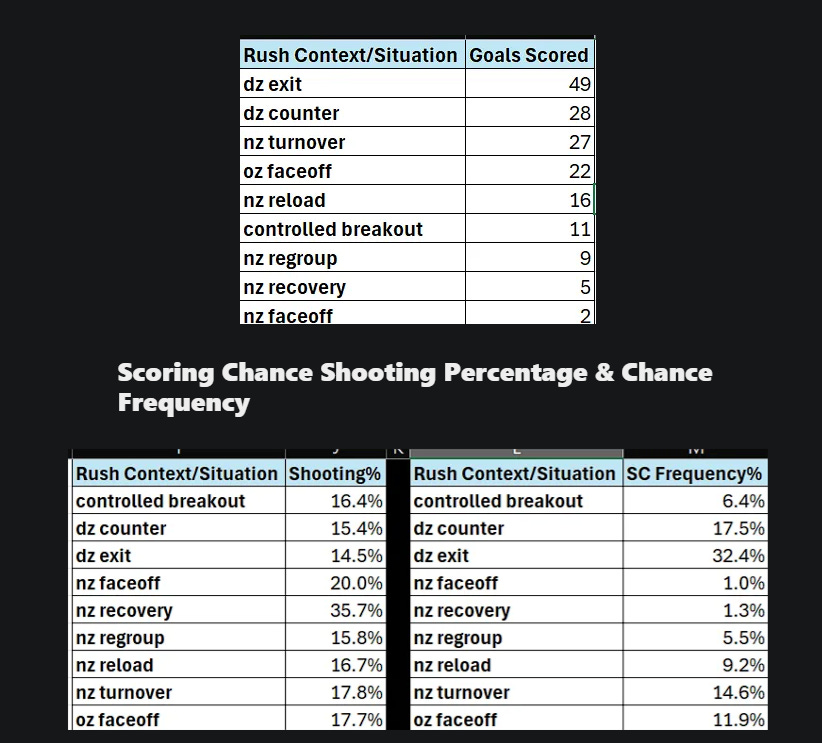

In 2013, a young Eric Tulsky and Corey Sznajder collaborated on a case study for the MIT Sloan Sports Conference, detailing the significance of entering the offensive zone with possession as opposed to dumping it in. It was concluded that successful carry-ins were significantly more conducive to overall offensive impact, as they led to a higher quantity of shot attempts taken as well as a higher shooting percentage. A carry-in advantage might seem inflated because turnovers weren’t being penalized enough in the stats. This was revolutionary at the time, being referenced as the origin of the league-wide shift to prioritizing rush offense. Fast-forward a decade later, the emphasis on creating offense from the transition is bigger than ever, but it’s focusing on controlled transitions from the defensive zone this time. A few weeks ago, the aforementioned Corey Sznajder wrote his post-mortems for the 2025 postseason, citing a new trend regarding where rush offense truly stems from:

“Most rush offense comes from the defensive zone off controlled exits, it’s the most reliable and repeatable way to attack off the rush. Forcing turnovers high in the zone for counter-attacks give you higher percentage shots but they happen at a lower frequency because of the risky nature behind it. Resetting for controlled breakouts & regrouping in the neutral zone typically don’t lead to a lot of goals and it’s becoming more suboptimal for teams to play this way now when you factor in how many more goals & scoring chances happen off turnovers. The frequency of counter-attacks and turnovers is the one thing that did change in the post-season, with defensive zone counters making up 22.7% of scoring chances off the rush in the regular season compared to 17.5% in the playoffs.”

A Shift In Philosophy

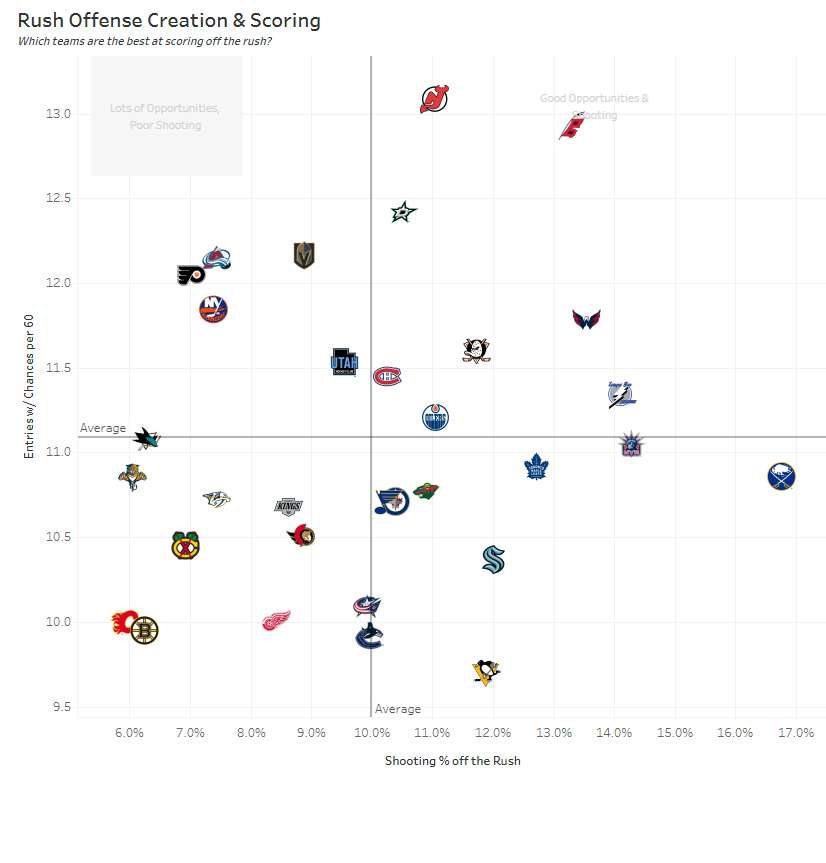

As seen above, scoring chance frequency is highest when the offense originates from the defensive zone counters and exits, thus proving how controlled zone exits are an invaluable component of creating offense off the rush. For a team known for its “over-reliance” on creating offense from the forecheck and cycling the puck, Tulsky’s first season as general manager saw the team produce their best numbers on the rush in the Rod Brind’Amour era by FAR.

Rod Brind’Amour finally gave the top-6 forwards the freedom to fully express themselves offensively and be creative, as Sebastian Aho and Seth Jarvis had their most proficient rush-offense season to date, while Martin Necas was doing signature Martin Necas things for the first ~50 games. Andrei Svechnikov and Jackson Blake were above-average at creating chances off the rush as well, but their below-average shooting percentages are the only thing separating them from the first set of the Canes. However, the common denominator of this sudden surge of offense? All the players I named (except Seth Jarvis) coincidentally were amongst the league’s best when it came to successfully exiting the zone with the puck. The lone exception in Seth Jarvis was a difficult one to wrap my head around, but there were two other factors to consider:

Sebastian Aho’s role as a free-moving fulcrum allowed him to get open in central areas of the ice, thus providing a better option for zone exits

Jarvis’ inefficiencies at carrying the puck out of the zone could be chalked up to his role on the Martinook-Staal line, which put more emphasis on flipping the puck out of the zone and chasing it.

He was a rare case where his stats were skewed because of who he was deployed with. There was also a set of players acquired mid-season that fit perfectly into this mold, as well.

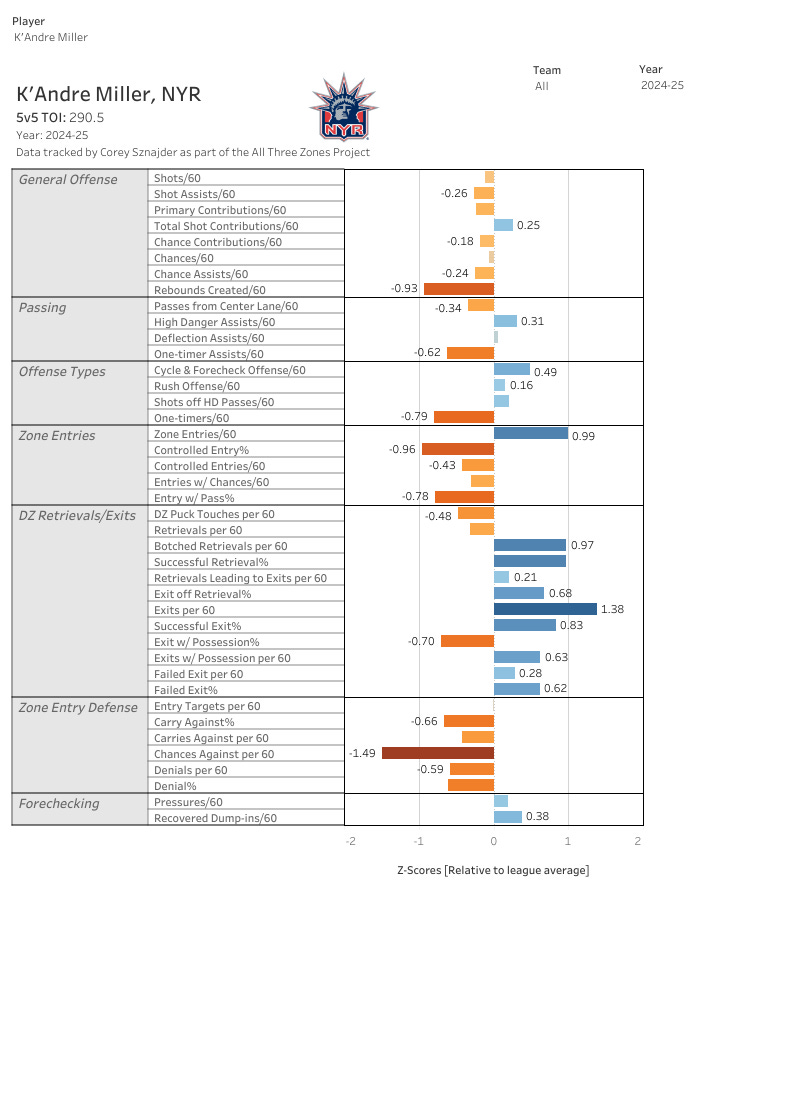

Taylor Hall and Logan Stankoven were one of the best forwards in the league when it came to consistently exiting the DZ with possession and carrying the puck into the OZ, while also being able to set up shop effectively in the offensive zone with the puck on their stick. Mark Jankowski, who was a complete afterthought at the time, isn’t nearly the same offensive threat as the two newcomers mentioned before him, but even he could control the puck out of danger on a consistent basis.

Regardless of what zone you’re in, the name of the game is controlling tempo, and the best way to control that tempo is to possess the puck and make smart decisions with it. All three of these mid-season acquisitions were more than capable of doing this, and performed admirably down the stretch.

Final Thoughts

Before I finish off this article, I’d like to shout out Corey Sznajder again for his contributions and inspiration for writing this piece. He does amazing work in the public hockey space, and I suggest you check it out and subscribe to him.

The Carolina Hurricanes have been at the forefront of the league when it comes to analytical usage since they hired Eric Tulsky to be a key member of their front office more than a decade ago. If the market is inefficient, they are more than willing to exploit it. They are an anomaly, with a front office that thinks differently, a fan base that acts differently, and a team that plays differently. So far, the Canes have made a pair of big splashes in two players that are so different yet whose greatest qualities are so alike in a way.

The Carolina Hurricanes have always had the same philosophy when it came to acquiring talent since Rod Brind’Amour took over: high-motor, defensively responsible forwards and capable, mobile defenseman that can activate at any given time. Now? They’re looking to evolve, to strike a balance the same way a very similar Florida team did a few years back, before becoming champions. It’s not necessarily about the system changing, but the on-ice personnel having the right skills to improvise when a play goes wrong or the system fails. A formerly predictable Canes team made moves to become more flexible, thus becoming harder to game plan around an already tough opponent. Will the ends justify the means, though? I guess we’ll just have to wait and see.